HUMANS AND SMART MACHINES AS PARTNERS IN THOUGHT?

All recordings of this workshop can be found HERE (and on my youtube play list)

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-ytDJty9ymIBGQ7z5iTZjNqbfXjFXI0Q&si=noZ7bPGz-uMt6jmm

Daniel Dennett: We are all Cherry-Pickers | |

Eric Schwitzgebel & Anna Strasser: Asymmetric joint actions | |

David Chalmers: Do large language models extend the mind? | |

Henry Shevlin: LLMs, Social AI, and folk attributions of consciousness | |

Keith Frankish: What are large language models doing? | |

Joshua Rust: Minimal Institutional Agency | |

Ned Block: Large Language Models are more like perceivers than thinkers | |

Paula Droege: Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing | |

Locations: | |

Location of the workshop: building: CHASS Int S, UC Riverside How to find: click on this LINK (https://campusmap.ucr.edu/?find=P5372) | |

Lunch break in Gather Town |

LINK (Password will be provided in the workshop)

|

Large language models (LLMs) like LaMDA, GPT-3, and ChatGPT have been the subject of widespread discussion. This workshop focuses on an analysis of interactions with LLMs. Assuming that not all interactions can be reduced to mere tool use, we ask in what sense LLMs can be part of a group and take on the role of conversational partners. Can such disparate partners as humans and smart machines form a group that takes not only linguistic actions (a conversation) but also other actions, such as producing text or making decisions? To address these questions, both the attributions of abilities to individual group participants and the ways in which the abilities of such groups can be described will be examined. This raises new questions for the field of social ontology, namely whether there are "social kinds" that are not exclusively constituted by humans. On the other hand, debates about the constitution of groups and their agency can contribute to analyzing the interactions of humans and smart machines. We expect to promote a dialogue among philosophers dealing with social groups, linguists, and artificial intelligence, respectively.

For preparation, click here to see the newest publications on LLMs

SCHEDULE (INTS 1113 - CHASS Interdisciplinary Symposium Room)

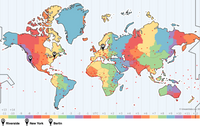

Riverside (PST) | New York | Berlin | 10 May | 11 May |

8.30 am | 11.30 am | 5.30 pm | Welcome & Café | Café |

9 am | 12 pm | 6 pm | Daniel Dennett (online): | Keith Frankish (online): |

10 am | 1 pm | 7 pm | Eric Schwitzgebel & Anna Strasser: | Paula Droege: |

11 am | 2 pm | 8 pm | Ned Block (online): | Joshua Rust: |

12 pm | 3 pm | 9 pm | Lunch (or / and Gather Town) | Lunch (or / and Gather Town) |

1 pm | 4 pm | 10 pm | David Chalmers (online): | Ophelia Deroy (online): |

2 pm | 5 pm | 11 pm | Henry Shevlin: | end for online participants |

3 pm | – | – | Walk & Talk | |

Conference Dinner |

Supported by

Daniel Dennett: We are all Cherry-Pickers

Large Language Models are strangely competent without comprehending. This means they provide indirect support for the idea that comprehension, (“REAL” comprehension) can be achieved by exploiting the uncomprehending competence of more mindless entities. After all, the various elements and structures of our brains don’t understand what they are doing or why, and yet their aggregate achievement is our genuine but imperfect comprehension. The key to comprehension is finding the self-monitoring tricks that cherry-pick amongst the ever-more-refined candidates for comprehension generated in our brains.

Eric Schwitzgebel & Anna Strasser: Asymmetric joint actions

What are we doing when we interact with LLMs? Are we playing with an interesting tool? Do we enjoy a strange way of talking to ourselves? Or do we, in any sense, act jointly when chatting with machines? Exploring conceptual frameworks that can characterize in-between phenomena that are neither a clear case of mere tool use nor fulfill all the conditions we tend to require for proper social interactions, we will engage in the controversy about the classification of interactions with LLMs. We will discuss the pros and cons of ascribing some form of agency to LLMs so they can at least participate in asymmetric joint actions.

- Strasser, Anna (2023). On pitfalls (and advantages) of sophisticated Large Language Models. preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.17511

- Schwitzgebel, Eric, Schwitzgebel, David, Strasser, Anna (2023). Creating a Large Language Model of a Philosopher.preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.01339

Ned Block: Large Language Models are more like perceivers than thinkers

I will argue that LLM processing corresponds much better to human perceptual processing rather than human thought. Perceptual representations lack logical structure and perceptual processing is not rule governed, simulating inference without being truly inferential. LLM representation and processing share these properties. Human thought is hierarchically structured—our thinking is characterized by dendrophyllia. But perception and LLM processing is not.

David Chalmers: Do large language models extend the mind?

tba

Henry Shevlin: LLMs, Social AI, and folk attributions of consciousness

In the last five years, Large Language Models have transformed the capacities of conversational AI agents: it is now entirely possible to have lengthy, complex, and meaningful conversations with LLMs without being confronted with obvious non-sequiturs or failures of understanding. As these models are fine-tuned for social purposes and tweaked to maximise user engagement, it is very likely that many users will follow Blake Lemoine in attributing consciousness to these systems. How should the scientific and philosophical consciousness community respond to this development? In this talk, I suggest that there is still too much uncertainty, cross-purpose, and confusion in debates around consciousness to settle these questions definitively. At best, experts may be able to offer heuristics and advice on which AI systems are better or worse consciousness candidates. However, it is questionable whether even this limited advice will shift public sentiment on AI consciousness given what I expect to be the overwhelming emotional and intuitive pull in favour of treating AI systems as sentient. In light of this, I suggest that there is value in reflecting on the broader division of labour between consciousness experts and the broader public; given the moral implications of consciousness, what kind of ownership can scholars exert over the concept if their opinions increasingly diverge from folk perspectives?

Keith Frankish: What are large language models doing?

Do large language models perform intentional actions? Do they have reasons for producing the replies they do? If we approach this question from an interpretivist perspective, then there is a prima facie case for saying that they do. Ascribing beliefs to an LLM gives us considerable predictive power. Yet at the same time, it is highly implausible to think that LLMs possess communicative intentions and perform speech acts. This presents a problem for interpretivism. The solution, I argue, is to think of LLMs as making moves in a narrowly defined language game (the 'chat game') and to interpret their replies as motivated solely by a desire to play the game. I set out this view, make comparisons with aspects of human cognition, and consider some of the risks involved in creating machines that play games like this.

- Frankish, K. (2022). Some thoughts on LLMs. Blog post at The tricks of the Mind (2 Nov) https://www.keithfrankish.com/blog/some-thoughts-on-llms

Paula Droege: Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing

Meaning, language, and consciousness are often taken to be inextricably linked. On this Fregean view, meaning appears before the conscious mind, and when grasped forms the content of linguistic expression. The consumer semantics proposed by Millikan breaks every link in this chain of ideas. Meaning results from a co-variation relation between a representation and what it represents, because that relation has been sufficiently successful. Consciousness is not required for meaning. More surprising, meaning is not required for language. Linguistic devices, such as words, are tools for thought, and like any tool, they can be used in ways other than originally designed. Extrapolating from this foundation, I will argue that Large Language Models produce speech in conversation with humans, because the resulting expression is meaningful to human interpreters. LLMs themselves have no mental representations, linguistic or otherwise, nor are they conscious. They nonetheless are joint actors in the production of language in Latour’s sense of technological mediation between goals and actions.

Joshua Rust: Minimal Institutional Agency

I make three, nested claims: first, while “machines with minds” (Haugeland 1989, 2) are paradigmatic artificial agents, such devices are not the only candidates for artificial agency. Like machines, our social institutions are constructed by us. And if some of these institutions are agential, then they should qualify as artificial agents. Second, if some institutions qua artificial agents also have genuine agency, that agency isn’t the full-blown intentional agency exhibited by human beings, but would fall under a more generic or minimal conception of agency. Moreover, since enactivists aim to articulate a minimal conception of agency that is applicable to all organisms, this suggests that enactivist accounts of minimal agency might be brought to bear on some institutions. The third claim concerns which enactivist notion of generic or minimal agency is relevant to the identification of corporate agents. Where some enactivists stress a protentive orientation to a persistence goal, others defend an account of minimal agency that only requires a model-free and retentive sensitivity to precedent. While enactivists have only glancingly applied these accounts of minimal agency to the question of corporate agency, I argue that those within the sociological tradition of structural functionalism have rigorously pursued the thought that corporate agents must be protentively oriented to a persistence goal. Criticisms of structural functionalism in particular and the protentive account of minimal agency in general motivate the conclusion that corporate agency is better construed in terms of the model-free and retentive account of minimal agency. I also claim that Ronald Dworkin (1986, 168) and Christian List and Philip Pettit (2011, 56) have defended versions of the idea that a sensitivity to precedent is a condition for institutional agency. Returning to the first claim, perhaps an investigation into the various modalities of artificial agency might be mutually illuminating. If a sensitivity to precedent is among the markers of genuine agency in institutional systems, perhaps this is also the case for more paradigmatic exemplars of artificial intelligence.

- Rust, J. (2022). Precedent as a path laid down in walking: Grounding intrinsic normativity in a history of response. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 1-32. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11097-022-09865-z

Ophelia Deroy: Ghosts in the machine - why we are and will continue to be ambivalent about AI

Large language models are one of several AI-systems that challenge traditional distinctions - here, between thinking and just producing strings of words, there, between actual partners and mere tools. The ambivalence, I argue, is there to stay, and what is more, it is not entirely irrational: We treat AI like ghosts in the machine because this is simple, useful, and because we are told to. The real question is: how do we regulate this inherent ambivalence?

- Deroy, Ophelia (2021). Rechtfertigende Wachsamkeit gegenüber KI. In A. Strasser, W. Sohst, R. Stapelfeldt, K. Stepec [eds.]: Künstliche Intelligenz – Die große Verheißung. Series: MoMo Berlin Philosophische KonTexte 8, xenomoi Verlag, Berlin.

- Karpus, J., Krüger, A., Verba, J. T., Bahrami, B., and Deroy, O. (2021). Algorithm exploitation: humans are keen to exploit benevolent AI. iScience 24, 102679.

SPEAKERS

*when you click on the pictures the website of the person opens

| |

Daniel C. Dennett, Tufts University, US (Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy) | |

Ned Block, NYU, US (Silver Professor; Professor of Philosophy & Psychology) | |

David Chalmers, NYU, US (Professor of Philosophy & Neural Science; co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness) | |

Ophelia Deroy, LMU Munich, Germany | |

Paula Droege, Pennsylvania State University, US | |

Keith Frankish, University of Sheffield, UK (Honorary Professor; Editor, Cambridge University Press) | |

Joshua Rust, Stetson University, US (Professor of Philosophy) | |

Eric Schwitzgebel, UC Riverside, US (Professor of Philosophy) | |

Henry Shevlin, University of Cambridge, UK (Associate Teaching Professor) | |

Anna Strasser, DenkWerkstatt Berlin, Germany (Visiting Fellow UC Riverside, Founder of DenkWerkstatt Berlin; Associate researcher CVBE) |